THERAPY GONE MAD

The Pastor vs. the Social Workers

A minister, charged with abuse for spanking

his son, slaps the state with a lawsuit.

BY JAMES TARANTO

The Wall Street Journal, Wednesday, September 15, 1999

![]()

"The rod and reproof give wisdom: but a child left to himself bringeth his mother to shame."

--Proverbs 29:15

![]()

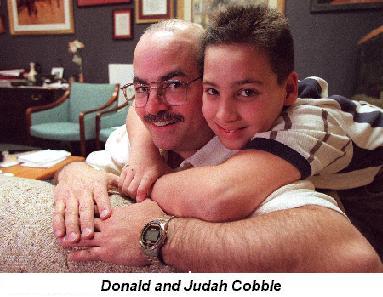

BOSTON--On Monday the Rev. Donald Cobble looked on as his lawyer defended him before the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court against allegations that he is a child abuser.

This is no Amirault case, with innocent people languishing in prison after conviction on charges that could not possibly be true. Mr. Cobble, associate pastor of the nondenominational Christian Teaching and Worship Center in Woburn, Mass., is a free man, and he openly acknowledges having done what he's accused of doing: punishing his 12-year-old son, Judah, by spanking him with a belt. He says he'll do it again if the need arises.

In March 1997 Mr. Cobble's adherence to the Proverbs led him and his family into the purgatory of a child-abuse investigation. A few months earlier Judah, then nine, had brought home a daily report from his teacher bearing two X's indicating bad behavior. "I went home, and I had to give Dad the note," Judah told me. "So he said, 'OK, you're going to get two licks with the belt because you got two X's.' "

These "licks" consisted of smacks on Judah's clothed buttocks with the soft end of a belt, which, Judah later told a social worker, left "pink marks on his body" that "would generally fade after ten minutes." In a word, spankings.

Judah stayed out of serious trouble until March, when his teacher told him she was giving him another bad report. "I said, 'No, don't do that--he'll spank me again.' " This set the bureaucratic wheels in motion. The teacher and a "behavioral management specialist," Mary Murphy Parkola, interrogated Judah about his father's disciplinary methods. Mr. Cobble and his wife, Lisa, were called to a meeting with the teacher, the principal and Ms. Parkola, who explained that they were filing a report with the Massachusetts Department of Social Services. (The Cobbles were then separated and have since divorced; Mr. Cobble has primary custody of Judah, their only child.)

That report, known as a "51A," recommended that the department undertake an investigation of possible abuse. A week later, a state social worker named Rena Ugol visited Mr. Cobble and then Mrs. Cobble, with whom Judah was living at the time. She interviewed all three, and a few days later filed a report saying her investigation supported the claim that Mr. Cobble had physically abused Judah. She also cited Mrs. Cobble for "neglect" because she had failed to prevent her husband from spanking their child.

Another social worker, April May, entered the picture in April. By June, Ms. May had completed her "45-day assessment" of the family. She presented Mr. Cobble with a "service plan." The document called for him, among other things, to "acknowledge harmful effects of physical abuse on Judah," "acknowledge responsibility for abusing Judah," "refrain from using physical discipline with Judah" and "attend individual therapy as a means of learning new, more appropriate ways of disciplining Judah."

Mr. Cobble refused to sign the service plan. Whereupon the state . . . did nothing. Mr. Cobble, however, decided to fight to clear his name. He challenged Ms. Ugol's finding at a Department of Social Services administrative hearing; the department, not surprisingly, sided with itself. Then he slapped the department with a lawsuit, and Superior Court Judge John Cratsley ruled against him. Mr. Cobble appealed, and the Supreme Judicial Court exercised its prerogative to take the case directly, bypassing the intermediate appellate court.

![]()

Mr. Cobble argues that the Department of Social Services has violated his constitutionally protected right to exercise his religion; the department denies it, asserting in its brief that it "investigates reports of abuse without regard to claimed religious justifications for conduct that places children at risk."

The record seems to contradict this claim. Both the 51A form and Ms. Ugol's report substantiating it make repeated references to the biblical basis for Mr. Cobble's disciplinary practices. Two examples stand out:

At the end of the 51A, the reporter (whose name is omitted from the redacted copy that is part of the court records, but who presumably is one of the three women from the school where all this started) gives her reason for recommending an investigation: "Both parents are physically disciplining the child and have admitted to teachers [that they] are using corporal punishment as dictated by Biblical Scripture."

And when Ms. Ugol enumerates her grounds for supporting the finding of abuse and neglect, she concludes with this: "It should additionally be noted that after the 51A report was filed, the parents transferred Judah from his public school to a Christian school. While this may have been done because parents prefer the latter school and felt the transfer was in the child's best interest, it is also possible that the transfer was an angry response by parents to remove the child from the venue which they believe was responsible for the 51A report/investigation. There is the potential that Judah's willingness or ability to disclose any further sense of 'unsafety' may have been compromised by this response from his parents."

It's chilling enough that Ms. Ugol regards the Cobbles' choice of a Christian school as a reason for suspicion. But consider what she suspects them of: being angry. They have just been accused, on the flimsiest of grounds, of committing child abuse--a horrific crime against their own son--and they might, we have reason to suspect, be angry at their accusers. Such gall!

![]()

When the Department of Social Services substantiated the charge of abuse against Mr. Cobble, it did not refer the case for criminal prosecution. It didn't even seek to declare him an unfit parent. Is it the department's view, then, that some child abusers are fit parents? In answer to this question, Assistant Attorney General Juliana deHaan Rice, who wrote the state's brief and argued its case Monday, says that Mr. Cobble was never declared a child abuser in the first place. The department found merely that, in her words, "reasonable cause existed to believe that this child had been subjected to the risk of physical abuse" (emphasis mine). She added: "It's a fairly low standard for supporting a 51A report."

Such legalistic niceties may warm the heart of an assistant attorney general, but they are cold comfort to a family that has been disrupted by a parade of social workers asking intrusive questions and pronouncing what sounds like a verdict of guilt. Child abuse is a despicable crime. When government agents throw the charge around as lightly as they do in Massachusetts, that too is despicable.

Next article: Ku Klux Klowns (10/26/99)